In un momento storico in cui la natura ha provato a riappropriarsi del mondo, in cui il nostro sguardo e le nostre percezioni possono dilatarsi e acuirsi anche a causa della necessità di accettare una visione mediata, il lavoro di un’artista come James Turrell ci invita a riflettere sulla consistenza delle nostre sensazioni. La sua arte funge da lente d’ingrandimento capace di guidare il nostro sguardo verso una contemplazione esteriore ed interiore del creato nell’infinita spettacolarità del suo essere. Questo processo si realizza a partire dallo studio di un fenomeno fisico fondamentale, vitale, costitutivo: la luce, elemento effimero in grado però di materializzarsi come presenza plastica che scolpisce la forma e colora lo spazio. Plasmando e dipingendo l’ambiente con la luce, il suo intervento è dedicato all’esperienza sensoriale soggettiva per mostrare l’infinita consistenza dello spettro luminoso attraverso i meccanismi di svelamento e ampliamento percettivo.

La pratica dell’artista (Los Angeles, 1943) deriva dall’approccio sperimentale di correnti come la Minimal Art, l’Optical Art e la Land Art da cui mutua la riduzione della forma all’essenzialità delle geometrie e all’assolutismo cromatico, l’interesse per i meccanismi di percezione dell’occhio nell’assorbimento di forme e colori, il rapporto con la natura che predilige l’eliminazione dei classici medium artistici. Intriso di questa cultura, Turrell diviene uno dei massimi esponenti del movimento Light and Space, che si afferma nella seconda metà degli anni ’60 a Los Angeles, caratterizzato appunto dall’interesse per le condizioni dell’ambiente circostante l’opera e dalle variazioni percettive causate dal rapporto tra spazio e luce. Lo studio dei fenomeni sensoriali in condizioni specifiche diventa il fulcro di una ricerca che si formalizza canalizzando flussi di luce naturale o artificiale all’interno di architetture e oggetti con l’ausilio di interventi strutturali o medium come neon, proiettori, lampade, LED, oltre all’uso di materiali trasparenti, traslucidi o riflettenti e delle più sofisticate tecnologie.

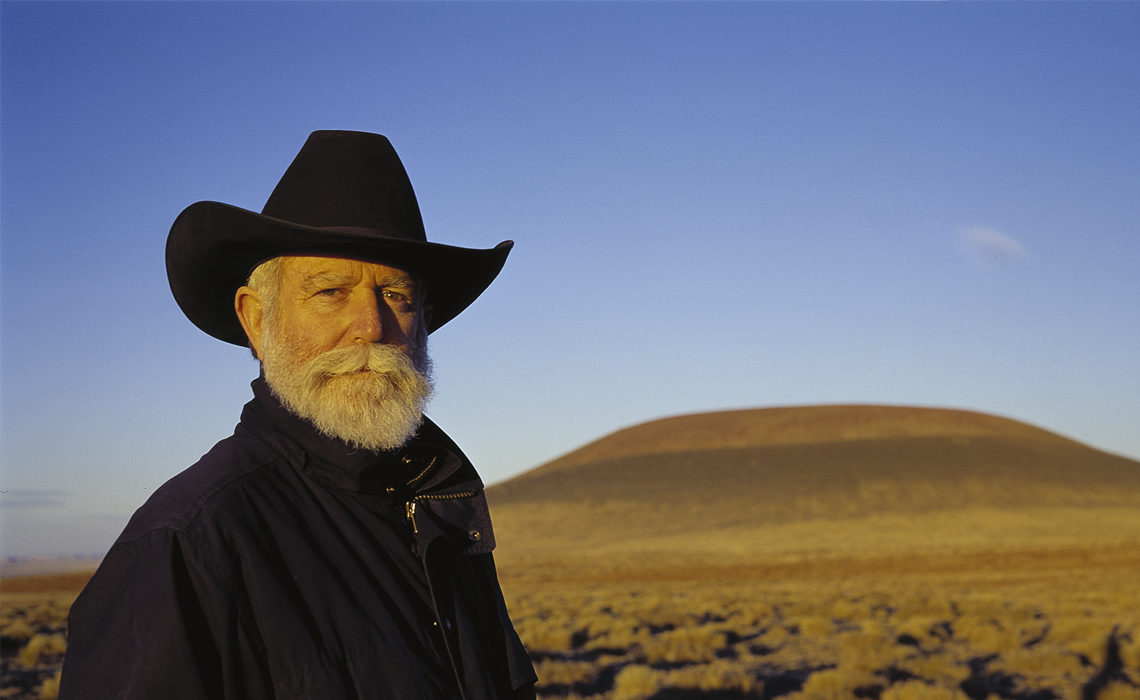

La predisposizione allo studio di questo fenomeno e la successiva applicazione in campo artistico ha una triplice origine: l’educazione giovanile, l’esperienza di aviatore e gli studi in psicologia percettiva, matematica e astronomia. I genitori di James Turrell sono quaccheri, seguaci di un movimento cristiano appartenente al calvinismo puritano, i cui fedeli si definivano in origine “figli della Luce”, convinti che quest’ultima rendesse tutto manifesto e visibile nella rivelazione mistica. Svincolata dal precetto religioso in quanto tale, questo tipo di formazione permette più ampiamente di comprendere l’importanza che Turrell assegna alla percezione personale di un fenomeno, quando afferma che è il singolo a dominarne le modalità perchè crea e costruisce la realtà in cui vive. I suoi primi lavori sperimentali partono da questi presupposti: i Projection Pieces (1966-1969), sono semplici figure geometriche disegnate dalla luce, che scandiscono e riempiono uno spazio fisico, ideati in principio aprendo una fessura in una finestra e permettendo solo a quantità di luce naturale controllata di invadere lo spazio in un punto specifico della stanza, e poi realizzati artificialmente proiettando un fascio di luce calibrato dall’angolo opposto della sala. La scelta di incanalare la luce artificiale per modellare un’immagine effimera si amplia quando l’artista decide di mescolare le fonti luminose, facendo filtrare contemporaneamente anche la luce naturale da tagli strutturali di edifici progettati ad hoc (interventi che prenderanno il nome di Structural Cuts), oppure creando percorsi al chiuso che conducono a finestre sul mondo, innescando sorprendenti relazioni tra esterno ed interno, l’induzione dell’artista alla casualità del creato.

Questa espansione della visione avviene quando da obiettore della guerra in Vietnam diventa un avido pilota e comincia a trasportare monaci buddisti tibetani al di fuori dello spazio aereo controllato dalla Cina. In quel periodo considera il cielo come il suo studio e la sua tela. Quando guardiamo dall’alto o da una certa distanza uno scenario, la nostra capacità di sentire ed isolare una porzione del mondo ci permette di vedere e provare una sensazione piuttosto che un’altra, di assottigliare la soglia tra realtà e immaginazione, a percepire la matrice spirituale del luogo che abitiamo.

Con i successivi interventi degli Skyspaces e nel complesso e grandioso progetto del Roden Crater, Turrell può plasmare la luce e lo spazio aggiungendo la condizione della variazione temporale, trattando lo spettro luminoso come se fosse una manifestazione tattile attraverso cui fugacità e fisicità si ricongiungono e ampliano il concetto di opera in molteplici dimensioni.

La presenza fisica della luce può spingere l’osservatore a sentirla come una materia preziosa. Un buco nel soffitto di una casa, capace di lasciare lo sguardo libero di spaziare verso un infinito incorniciato dal bordo bianco dell’intonaco di una parete, può manifestarsi come opera d’arte. Gli Skyspaces (il primo viene realizzato nel 1974 in Italia a Villa Panza) sono costituiti da semplici interventi di apertura di un soffitto per canalizzare la vista verso il cielo e dischiudere la limpida essenza dell’empireo. L’entrata in spazi chiusi per sollecitare la percezione dello spazio aperto, rivela come si possa diversamente contemplare il passaggio da uno stato luminoso all’altro. L’artista riesce a rendere più intenso un colore in base al contesto, a dimostrare che il cielo è bianco, azzurro, blu, ma anche indaco. La nostra concezione di esso è mediata da un ambiente che definisce e determina la visione di uno spettro che si fa colore e mantiene inalterate le stesse intrinseche qualità costitutive, tangibili anche se dominate dall’inconsistenza fisica.

Qualche anno dopo la formalizzazione degli Skyspaces, l’artista approfondisce gli studi di psicologia analizzando il fenomeno ottico noto come effetto di Ganzfeld: la privazione sensoriale che determina la perdita totale della percezione di profondità. I Ganzfeld di Turrell sono sale invase da luci colorate rarefatte in cui l’unica forma percepibile è un rettangolo luminoso composto dello stesso colore che riempie le stanze, all’interno delle quali si perde la cognizione del tempo e dello spazio. L’unico elemento codificabile resta la luce che manifesta la sua consistenza fisica grazie alla compressione nello spazio chiuso. L’artista spinge ad interrogarsi non su quello che viene visto ma sul modo di percepire la densità della luce che attraverso le sue installazioni si materializza come presenza riempitiva.

L’arte di Turrell necessita della fruizione diretta da parte dello spettatore e può essere difficilmente mediata e veicolata dalla riproduzione video o fotografica: è un impianto percettivo studiato e strutturato per approfondire la sensorialità dell’esperienza.

In an historic moment when nature has tried to regain the world, when our gaze and our perceptions can expand and escalate, also because of the need to accept a mediated vision, the work of an artist such as James Turrell, invites us to reflect on the consistency of our sensations. His art functions as a magnifying glass capable of guiding our glance toward an external and internal contemplation of the creation in the infinite spectacle of its being. This process is realized beginning from the study on fundamental, vital, constitutive physical phenomenon: light, fleeting element capable however of materializing itself as a plastic presence, sculpting shape and coloring space. Shaping and painting the environment with light, his intervention is dedicated to the subjective sensorial experience, in order to show the infinite consistence of the light spectrum through mechanisms of perceptive unveiling and enlargement.

The practice of the artist (Los Angeles, 1943) derives from the experimental approach of currents such as Minimal Art, Optical Art and Land Art, from which he borrows the reduction of form to the essence of geometry and the chromatic absolutism, the interest in the mechanisms of the eye perception in absorbing shapes and colors, the relationship with nature which favors the removal of the classic artistic medium. Imbued with this culture, Turrell became one of the greatest representatives of the Light and Space movement, which was established in the second half of the 1960s in Los Angeles, characterized indeed by the interest in the conditions of the environment surrounding the piece and in the perceptive variations caused by the relationship between space and light. The study on the sensorial phenomena under specific conditions becomes the focal point of a research which becomes formalized channeling fluxes of natural or artificial light inside architectures and objects with the support of structural interventions or media such as neon, projectors, lamps, as well as the use of transparent, translucent or reflecting materials and the most sophisticated technologies.

The predisposition towards the study on this subject and the following application in the art field has a triple origin: youth formation, the experience as an aviator and the studies on perceptive psychology, math and astronomy. James Turrell’s parents are Quakers, followers of a Christian movement belonging to puritan Calvinism, whose devoted originally defined themselves as “children of Light”, certain that the latter makes everything clear and visible in the mystic revelation. Released from that religious precept, this kind of formation allows to more clearly comprehend the importance that Turrell gives to the personal perception of a phenomenon, when he states that it is the single who dominates modality, because he creates and builds the reality he lives. His first experimental works begin from these assumptions: the Projection Pieces (1966-1969), are simple geometric figures painted by light, which mark and fill a physical space, originally devised by opening a fissure on a windows and allowing only a small quantity of controlled natural light to invade the space, in a specific point of the room, and later artificially realized by projecting a calibrated beam of light from the opposite side of the hall. The choice of tunneling the artificial light to shape an ephemeral image is amplified when the artist decides to mix the light sources, by allowing natural light to leak at the same time through structural cuts in building created ad hoc (interventions that will take the name of Structural Cuts), or by creating paths in the darkness leading to windows on the world, triggering surprising relationships between external and internal, the induction of the artist to the randomness of creation.

This expansion of the vision happens when, as an objector to the Vietnam War he becomes an avid pilot and begins to carry Tibetan Buddhist monks outside of the airspace controlled by China. During that period, he considers the sky as his atelier and his canvas. When we observe from above or from a certain distance a scenario, our ability to feel and isolate a part of the world allows us to see and feel a sensation more than another, to reduce the distance between reality and imagination, to perceive the spiritual matrix of the place we inhabit.

With the later interventions, the Skyspaces and the complex and majestic project of the Roden Crater, Turrell is able to bend light and space adding the condition of temporal variation, treating the light spectrum as a tactile manifestation through which transience and physicality reunite and expand the concept of piece in several dimensions.

The physical presence of light can lead the observer to feel it as precious matter. A hole in the ceiling of a house, that allows the gaze to freely space towards an infinite framed by the white border of a plastered wall, can occur as an art piece. The Skyspaces (the first one realized in 1974 in Italy, in Villa Panza) consist of simple interventions of openings in a ceiling to guide the view towards the sky, opening to the clear essence of the empyrean. The entrance in closed spaces to stimulate the perception of the open space, reveals how differently we can contemplate the environment from a light condition to another. The artist makes a color more intense depending on the context, as a demonstration that the sky is white, light blue, blue, but also indigo. Our conception of it is mediated by an environment that defines and determinates the vision of a spectrum that becomes color, fully preserving the same intrinsic constitutive qualities, tangible even if dominated by a physical inconsistency.

Some years after the formalization of the Skyspaces, the artist delves into the studies on psychology, analyzing the optic phenomenon known as Ganzfeld Effect: the sensorial privation determining the total loss of depth perception. Turrell’s Ganzfeld are halls invaded by rarefied colored lights where the only perceivable shape is a light rectangle made of the same color invading the room, within which the sense of time and space is lost. Light remains the only codifiable element, manifesting its physical consistency thanks to the compression inside the closed space. The artist leads us to ponder not on what is seen but on how to perceive the density of the light that, through his installations, materializes as a filling presence.

Turrell’s art needs the direct fruition of the the audience and is difficult to mediate or convey by video or picture; it is a perceptive system, ideated and organized to explore the sensoriality of experience.

No Comments