Novantatremiliardi di albe è un’opera site specific del 2015 che si trova ad Anacapri e che, per diverse volte, in tempi diversi, mi ha portato sull’isola.

L’idea dell’opera nacque durante un soggiorno a Capri nel luglio del 2014. Il sole che tramontava sul mare con la sua puntuale quotidianità, mi fece pensare al continuo ripetersi degli eventi al di là della presenza di noi osservatori. La bellezza del tramonto non richiede i nostri sguardi ma quelli della roccia di cui è fatta l’isola, che da lunghissimo tempo guarda il ripetersi del tramonto ogni giorno e ancora continuerà a guardarlo per le prossime ere.

Pensai che dall’altra parte del mare, in Sardegna, precisamente in Gallura, altre rocce guardano uno spettacolo opposto, l’alba, anche lì da tempi così lunghi che al confronto il nostro tempo umano è nulla. Bisognava solo andare in Gallura, cercare un masso che da sempre fosse stato su qualche collina a guardare il sole che sorgeva dal mare, portarlo a Capri e posizionarlo in modo che, dopo innumerevoli albe, potesse guardare il tramonto. Occorreva anche una base che accogliesse il masso, una base di bronzo. Di solito per i monumenti è il contrario che avviene, è la pietra che fa da base al bronzo della statua. A dicembre del 2014 il masso di granito sardo aveva effettuato il suo viaggio per arrivare a Capri dove aveva trovato ad attenderlo una base di bronzo bianco e il suo primo tramonto dopo miliardi di albe.

Quest’opera, così impegnativa da un punto di vista realizzativo, racchiude molte tematiche ricorrenti nel mio lavoro: il nostro rapporto con il tempo, l’uso dei materiali con cui è fatta la scultura e il loro significato, il nostro rapporto con lo spazio che ci circonda.

Il rapporto con il tempo ritorna anche in Angolo Stanco, un’opera recente del 2018. Una scultura a forma di angolo in metallo nero accoglie al suo interno un uomo o una donna di 78 anni, tanti quanti la distanza tra il tempo presente e la morte di Walter Benjamin a Portbou, in Spagna, al confine con la Francia. Quando qualcuno si avvicina alla scultura il performer inizia a parlare dicendo il suo nome, la data di nascita e raccontando un po’ della sua vita. L’opera è la concretizzazione della distanza temporale tra un evento definitivo, la morte di Benjamin, e l’oggi. L’idea dell’anniversario della celebrazione di una morte è analizzata attraverso il suo contrario, una vita, quella del performer, che è iniziata quando Benjamin è morto.

Il titolo si riferisce a un elemento fondante dell’architettura, l’angolo, che è stanco come Benjamin quando decise di porre fine alla sua esistenza a Portbou. La scultura è destinata a cambiare nel tempo, perché ogni anno che passa aumenterà l’età del performer ospitato nell’angolo, così come aumenta la distanza tra il presente e la morte di Benjamin; a un certo punto non ci saranno più persone che per età potranno entrare nell’angolo e la scultura resterà disabitata, una forma che racchiude storie.

L’uso dei materiali e come questi diano significato all’opera, come ad esempio nel caso di Novantatremiliardi di albe il masso di granito con la sua provenienza e la sua vecchiezza, ritorna anche in Metro cubo di marmo con metro lineare di cenere sempre del 2018: un cubo di marmo di un metro per lato, con un solco lineare sul lato superiore lungo un metro, largo un centimetro e profondo un centimetro. Questo solco nel marmo è riempito della cenere dei sigari fumati da me. L’opera nasce da assonanze e dissonanze tra i due materiali che la compongono: è una scultura fatta sia per togliere (il taglio) che per mettere (la cenere). Il colore della cenere dei sigari è grigio come il grigio delle venature del marmo. Le venature naturali create dal tempo nel marmo sono curvilinee, la linea riempita di cenere è dritta. La venatura è curva come la natura, la cenere è in linea retta, innaturale. Le venature del marmo e la cenere del sigaro hanno a che fare con il tempo, il tempo lungo della pietra e quello corto degli uomini; entrambi sono residui, tracce di un passaggio, la cenere è il residuo di un respiro, uno scarto, la venatura è la traccia di una forza enorme e costante. Il marmo è pesante, 2700 chili e più, la cenere leggera, 20 grammi e meno. Il marmo è resistente, la cenere è volatile ma indistruttibile. Il marmo può diventare polvere leggera come cenere, la cenere può schiacciare come la pietra.

Anche in quest’opera, oltre alla questione della significanza dei materiali, ritorna il tema del tempo. Un’opera non contiene mai un’unica tematica o un unico significato ma tanti e tanti altri ne aggiungono gli sguardi di chi la osserva.

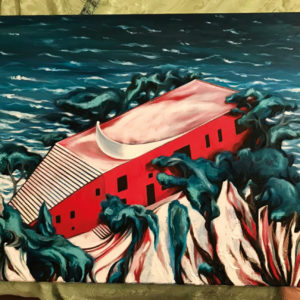

Spesso mi sono interessato al rapporto tra l’uomo e il paesaggio che lo circonda o che deve attraversare, come nel caso dei lavori sulla questione dei flussi migratori contemporanei, una storia di oggi che si ripete da sempre.

Riduzione di mare è un’opera del 2012 che tratta di questo tema. E’ un blocco di sale del peso di 34 kg (quantitativo ottenuto dall’evaporazione di un metro cubo di acqua di mare) che ogni volta che viene esposto, e per tutto il periodo di esposizione, viene leccato da un performer che, sotto dettatura di un altro performer, lo lecca con l’intento di sovrascrivervi un testo tradotto in codice morse, toccandolo con dei colpi di lingua corti, corrispondenti al punto, e lunghi, corrispondenti alla linea. Il testo che il performer “trascrive” sul blocco di sale è un documento compilato dall’organizzazione olandese United for Intercultural Action che consta dell’elenco delle persone morte nel tentativo di emigrare nella sola Europa. Questo elenco prende in esame esclusivamente le morti di cui i mass media hanno dato notizia partendo dal 1° gennaio 1993 e in continuo aggiornamento. La trascrizione in morse sul blocco di sale richiede tempo e un costante ricambio di performer perché la stessa persona non può assumere più di un determinato quantitativo di sale al giorno. Al termine della performance, se mai si riuscirà a terminare la scrittura-lettura, Riduzione di mare apparirà come risultato di un processo di erosione e cambiamento, mutato dal movimento umano e dai suoi umori, lacerto di un tempo trascorso ma ancora in divenire.

Francesco Arena: Novantatremiliardi di albe

Francesco Arena

Novantatremiliardi di albe is a 2015 site-specific work located in Anacapri that has brought me to the island several times.

The idea for this piece came during a stay in Capri in July 2014. The sun fading into the sea in its daily routine, made me think about the continuous repetition of events beyond the presence of the observers. The sunset’s beauty doesn’t need our gaze, but rather the gaze of the rocks that form the island, that for a very long time has been watching every day the recurrence of the sunset and will continue to watch it for the next eras.

I thought that, on the other side of the sea, In Sardinia, Gallura, precisely, other rocks where watching the opposite show, the dawn, from such a long time, that in comparison our human time is insignificant. I only needed to go to Gallura, look for a rock that had always been located on a hill, watching the sun rising from the sea, bring it to capri and place it so that, after countless dawns, it could watch the sunset. I also needed a pedestal to place the rock, a bronze pedestal. In December 2014, the Sardinian granite rock finished its journey to reach Capri, where a pedestal of white bronze and its first sunset were waiting for it, after billions of dawns.

Such a demanding work to realize, includes many recurring themes of my works: our relationship with time, the employment of materials and their meaning, our relationship with the space surrounding us.

The relationship with time is also featured in Angolo Stanco, a recent work realized in 2018. An angle-shaped sculpture made of black metal accommodates a man or woman of 78, the same years there are between the present time and Walter Benjamin’s death in Portbou, Spain, on the border with France. Every time someone approaches the sculpture, the performer starts talking, telling his name, date of birth, and saying something about his life. The work is the actualization of the temporal distance between a determined event, Benjamin’s death, and the present. The idea of a death anniversary, its celebration, is analyzed through its opposite, life, the life of the performer, that had begun when Benjamin died.

The title is a reference to a fundamental element in architecture, the angle, that is as tired as Benjamin was when he decided to end his life in Portbou. The sculpture is destined to change with the passage of time, as every year the age of the performer sitting in the corner will increase, as will increase the distance between the present time and Benjamin’s death: at one point, there won’t be any adequately-aged people that will be able to sit in the corner and the sculpture will remain inhabited, a form that contains stories.

The employment of materials and how they give meaning to the piece, as in Novantatremiliardi di albe. The granite rock, with its origins and old age, also returns in Metro cubo di marmo con metro lineare di cenere also realized in 2018: a marble cube with a meter-wide side, featuring a linear groove on the upper side, one meter long, one centimeter wide and one centimeter deep. This groove in the marble is filled with the ash of the cigars I smoked. The piece was born from the assonances and dissonances between the two materials that compose it: it is a sculpture made for removing (the cut) and adding (the ash). The cigar’s ash is grey, like the grey veining on the marble. The natural veining on the marble created by the passing of time are curved, the line filled by the ash is straight. The veining is curved like nature, the ash is a straight, unnatural line. The marble’s veining and the cigar ash concern time, the lengthy time of the stone and the short time of Man: both are leftovers, traces of a passage, ash is the leftover of a breath, a scrap, the veining is the trace of an enormous and constant strength. The marble is heavy, 2700 and more kilograms, the ash, light, less than 20 grams. The marble is sturdy, the ash is fleeting yet indestructible. The marble can become a dust, light as ash, and the ash can crush like a stone.

In this work as well, in addition to the importance of materials, the theme of time is present. A work of art can never feature a single theme or a single meaning, but should feature several, and the observers add many others.

I’ve been often interested in the relationship between man and the surrounding landscape or the landscape he must overcome, as in the case on the works on contemporary migration, a current story that has been eternally repeated.

Riduzione di mare is a 2012 work concerning this theme. It’s a salt block weighing 34 kilograms ( an amount obtained by evaporating of a cubic meter of sea water), that every time is exhibited, and for the entire exhibition period, is licked by a performer who, following the dictation of another performer, licks it with the intent of writing a text translated into Morse code, touching it with short blows, the point, and long blows, the line. The text the performer “transcribes” on the salt block is a document published by the Dutch organization “United for Intercultural Action”, and it contains the list of the people who have died trying to emigrate toward Europe only. This list takes into consideration only the deaths that have been reported by the mass media, starting from January 1st, 1993, and it is continuously updated. The Morse transcription on the salt block requires time and the constant replacement of performers, as the same person cannot assume more than a given quantity of salt per day. At the end of the performance, if we are ever going to complete this writing-reading, Riduzione di mare will appear as the result of a process of erosion and changing, transformed by the human movement and its feelings, a fragment of a past time still in the making.

No Comments